The Inside Track: A Conversation with Red Hook Crit’s David Trimble

The 2019 State of the Sport Series on the To Be Determined Journal is presented by Castelli.

Words by Clay Jones & Erwin Kersten-Johnston; Photos by Sebastian Vidal & Daghan Perker

In recent months our State of the Sport series has examined everything from traditional categorized road racing, to gravel rides, to a thorough data analysis of the life-cycle of a bike racer. We’ve also looked at things from the perspective of the Race Directors. What’s been missing is arguably one of the most popular, controversial, and exciting additions to cycling over the last decade: fixed gear racing. Until now.

We continue our series with a conversation with Red Hook Crit founder and organizer David Trimble. The man will need no introduction, nor will the event. Most who follow cycling (and perhaps, more importantly, some who don’t) will know the story of how the first iteration was basically David’s birthday party spent racing fixed gear bikes on the streets of Brooklyn.

Fast forward 10 years, and the event may as well be the SuperBowl of cycling. In a sport that is struggling across the board to draw in people and money, the event has been a beacon of light, drawing in record crowds for Red Hook Crit BK10 and attracting racers and sponsors from across the globe.

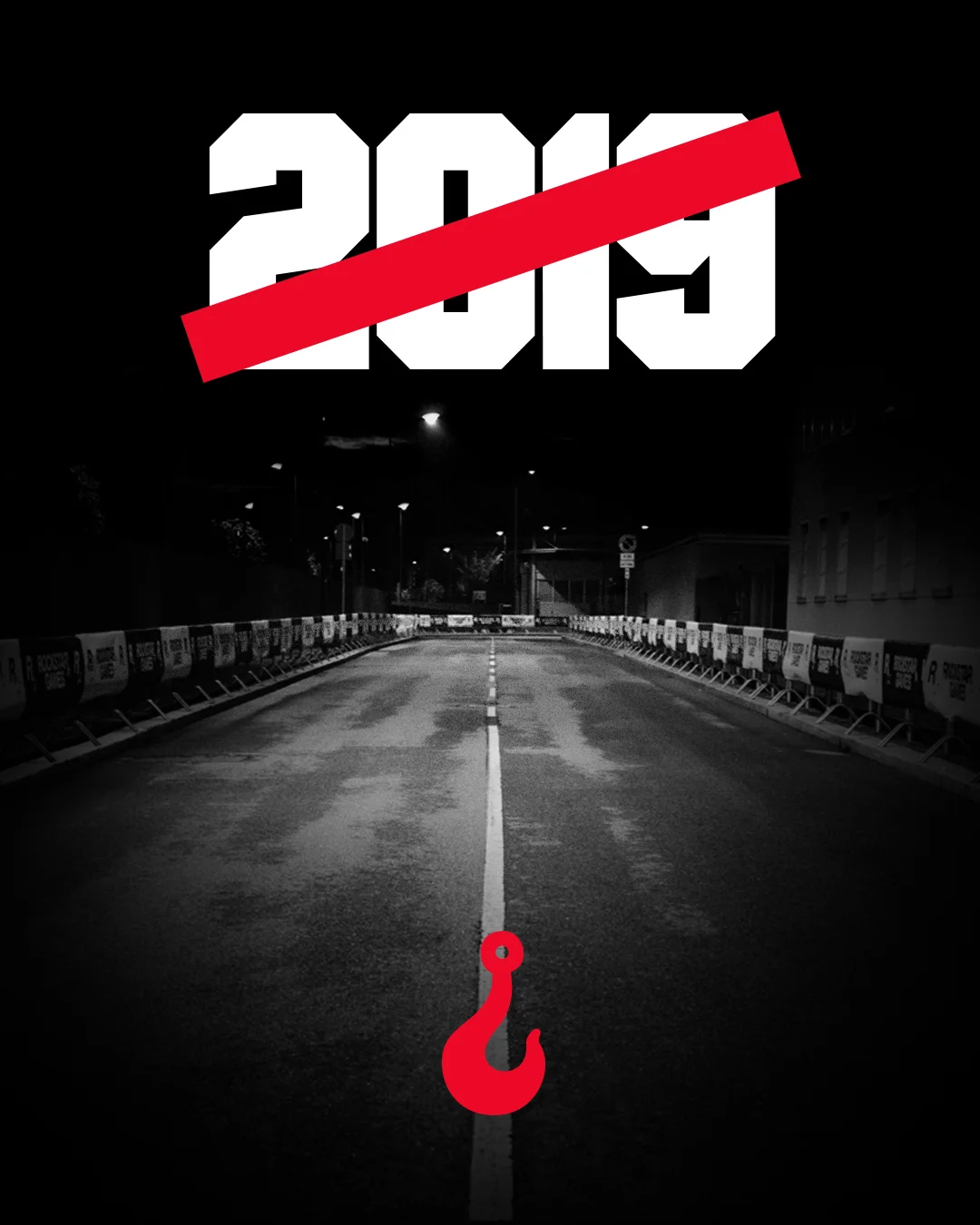

But then came a shocking turn of events: the Series, which had grown to three international races in 2017 – London, Barcelona and Milan – in addition to Brooklyn, had to cut London and Barcelona out of the 2018 calendar. Anyone that listened carefully to Trimble’s 2018 RHC Milan press conference knew the future of RHC wasn’t necessarily as certain as its popularity would suggest. It still broke the hearts of many fans when on Valentine’s Day this year, RHC announced via Instagram that after careful consideration of all the options, they’d be taking 2019 off to focus on raising support and developing plans for the continuation of the Red Hook Criterium Championship.

A few weeks after the news, we sat down over coffee with David to find out how he’s doing, what’s driving him, and what his view is on the future of our sport.

Part I: Organizing

In the first stretch of the interview, we focused on the design and development of races that can draw in folks outside of cycling, both in-person and online, or on TV. We left this part of the conversation thinking about differences between the local, amateur races that TBD competes in, and the big, high-production (occasionally pro-only) events that seem to be gaining traction. We were also thoroughly impressed by David’s approach to the craft of race organizing and directing and the commitment necessary to grow an event from a birthday party to an international sensation.

TBD: What are your thoughts on the local racing scene? How has it changed since RHC got its start?

DT: I'm not sure how much they've changed. I think, if anything, they might have become a little less exciting over the years. Grant's Tomb – people used to get really amped up about it.

I'm really disconnected from the local racing scene. I've done a couple of Prospect Park races over the years, and they just, they seem like they're... ageless? To me, it's like softball league, basically – not really an event. No one outside of the race really cares who wins; people are doing it for personal reasons more than anything else. That's part of the reason that, when I started developing the Red Hook Crit, I was inspired more by the Alleycat culture than by what was happening in local, sanctioned road racing events. [Sanctioned road races] are kind of depressing in a way – for me, racing is exciting because there's hype around it and like people get into the racing and care who wins… and people start to feel pressure from the races.

Is the NY Velocity site still around?

TBD: It is, but it’s not the same as it once was.

DT: It was so bad! You would win a race, and everyone would post comments saying “Oh you're a sandbagger” or “Yeah, but this person wasn't there.” I didn't feel anything positive about the community through that platform.

TBD: What do you think the factors were in RHC’s growth from a party to a global series?

DT: Fundamentally: it brought all sorts of people outside of cycling into the sport. But it was also something that inspired a lot of creativity. It’s happening late at night. It's really visually spectacular. New York City is full of the best photographers in the world, and they all came out and started shooting it. We had the best graphic designers in the world making cool posters around it. And there was a party where there's like, actual people outside of the cycling world there.

So I think just making it inclusive to people outside of the cycling scene allowed it to start growing. It developed as a cultural event as much as, if not more than, an amateur sporting event.

TBD: With that in mind, where do you think the sport is headed?

DT: I mean, it's such a big sport. Traveling around the world, I’ve seen it in different places, and I don't think it's necessarily dying out, but maybe it's getting spread too thin. I don’t try to study the health of other specific races too much, but fixed gear racing is definitely growing fast. There’s more and more of them around the world – you know, every country in Europe has their own series at this point.

I do think there is a problem. Once your event gets to a certain size, you have to bring more money into it and professionalize it. I think that's something that's never happened with the races in New York. I went to Grant's Tomb one year, and there wasn't even a finish line. It's just like, how little effort can you put into this.

But it's hard because at the same time, I devoted my life to the RHC for 10 years. Every day was killing myself to try to make it better. And I don’t think there's that level of dedication from most race organizers.

TBD: We’ve heard you’re more excited about Neversink-style races than even crits. True or false?

DT: Neversink has always been an exercise in putting on a race that I would want to compete in. No pressure from sponsors. No major financial burdens. Yeah, just to be an event that I think would be really fun.

I'm fanatical about designing routes. Part of it is just being able to design a super interesting race course: I was obsessive over last year’s Neversink course, and then seeing everyone race it on the day is really fulfilling. And the setting is so amazing – a brilliant escape from being in front of the screen.

TBD: What's your process for designing a course?

DT: I mean RHC is on another level. To design the course for Brooklyn last year, I spent at least four months of just studying it and going into the venue, coming out with all these different concepts and testing it, and having architects draw up plans.

TBD: What drove the changes last year?

DT: A combination of things. I like to change it every year that I can: What would make it spectator friendly? What would make it safe enough, but not too safe? What would make the festival area work well?

TBD: So is it production value vs sporting value?

DT: I’m always thinking about what will make for a thrilling race in the end.

We took steps along the way to professionalize the operation. We worked with teams that were responsible for building our courses based on our designs. We had to recognize that the race is so crazy, so high adrenaline, that a top priority is being able to control the circuit.

From my motorsports days, I know how important the course marshals are. If there's a crash, the flag goes out immediately. Compare that to any other bike race. If you see some of the insane videos from USA Cycling Crits, there will be a crash, and then they just run into it three laps in a row, because no one knows how to stop the race. So by design we are able to really control the course tightly, and get the best people to do it.

TBD: When it comes to cost of production, is permitting the biggest part?

DT: Staff. Staff is by far the biggest part. And a lot of that is bringing these marshals over. We used to get marshals locally in each city, first as volunteers, and then we would pay them... And then we realized, “Oh, wait. They're only doing it once a year. They're not learning how to do this well.” So we hired a team of the same people to go to every race. Going to all the races makes sense, but it just costs a lot. So every time we made the race better, it costs a lot more money.

TBD: Was there a process for capturing that knowledge and making the whole thing better?

DT: You know, after every race, no matter how successful it was, I would wake up on Monday kind of depressed. Just thinking about all the things that went wrong. In London, a spectator jumped on the course: why did he do that? How can we stop that in the future?

So after every race we make a five page list of all the problems and then we figure out if these things were just flukes, or can we solve it?

To give you a specific example: I decided to start bringing the same marshal team to every race, as a result of what happened after a big crash in Barcelona 2015, with three laps to go: one of the marshals panicked and called for a red flag. Later, we looked at the video, and actually, we could have kept the race going. He wasn't experienced enough to make that decision to keep the race going, because the crash looked really bad. Once you have the same marshals doing it, race after race after race, they would gain more experience and be able to make better calls.

TBD: Any other good examples?

DT: Hundreds probably! Some of them are super obvious: we used to not have photo-finish cameras, because we were just trusting the timing chips. Next thing you know, we had a really close sprint finish in Milan 2013, where it was so close between third and fourth, and we realized the timing chips didn’t really work for that. We ended up getting there, but I could write a book about every step of the way.

TBD: We hear from race directors across the US, and some are really concerned learning that RHC wasn’t continuing this year. Do you have any thoughts to share or advice from your experience?

DT: I think it depends on what scale the events are already at. Take Grant's Tomb here in New York: I think there's a real risk in trying to grow it. CRCA actually asked me this year if I wanted to help direct it, and I determined that they should keep it at the level and exposure it is. Because right now they're not even paying for the police – their costs are super low! And the second you start growing, it is just going to turn into this monster. The police could easily charge them $100,000 for the day, and they currently don't charge them anything. So once you get a big sponsor, the police are going to see a corporate logo, and they're gonna want their money.

For other organizers, especially fixed gear organizers, I think they need circuits that are safe first and foremost. A lot of them are just hacking together these courses and not really thinking about how to make the event safe. Usually those events work well when there's 50 people racing, but all of a sudden, they have 200 entries, and it's a different story.

They’re keeping themselves from growing their own event. Because going through a three foot wide opening between two stone walls might be fine at first, but once the race becomes bigger and more important, people are going to take bigger risks. I don't ever give blanket advice, but safety and making sure your race rules and scoring make sense, could be some. And you know...have a finish line. And perhaps lastly, be honest to yourself as a director about what it is and not trying to make it something that it can’t be.

TBD: If after considering all options, RHC doesn’t continue next year, what does the future hold for David Trimble?

DT: Ha, good question! With Red Hook, I've already accomplished way more than I ever planned. I never wanted to be a race organizer or work on events. I'm not quite sure yet what I would do right now. This year, I'm working back with my uncle at the architecture firm and working on another project.

At the same time, I’m doing everything I can to bring Red Hook back, but beyond that I'm not quite sure what my professional passion will be.

I do think I would like to keep being involved in racing: I learned a lot from the first 11 years that I can apply and get better in the future.

TBD: You’ve said before you’re not a fan of broadcasting too much live data in bike races. You don’t think people get excited by it?

DT: You care about lap times, right? But do you care about brake temperatures? No. And to me, brake temperature is like the same thing as how many watts or how many horsepower the motor is putting out at the same time – it's technical. Someone might be doing 600 watts and all of a sudden they're coasting, and it’s down to zero and it’s a bit all over the place. So to me it is a lot more interesting if they could show more clearly the space between different groups. Like the delta times and how fast a group is closing on another group. Or, they never have a shot where you can see the breakaway and the peloton; they just have two separate shots and it's hard to get a sense how far ahead someone really is.

TBD: Several friends are really into Peloton right now, and for the first time experiencing a power meter. Do you think there’s something there that can help people understand where you are, compared to other human bodies?

DT: Peloton. It’s exercise, that’s what it is. I guess there’s something there [with the power comparison], but like if you're thinking about broadcast and entertainment, then most people who watch Formula One aren’t Formula One drivers. So I think if cycling gets to the point where it's a real mainstream sport that people watch, most of them aren't going to be bike racers. 300 or 400 watts, people just want to watch something that's really exciting.

TBD: Right, so RHC 2021, live broadcasted on YouTube, will not display power?

DT: No. I do not care about that. That’s not what will make it exciting. Think about Moto GP: they're like 20 seconds a lap slower than Formula One, but it looks like crazy super fast.

TBD: Same thing goes with the zip line tracking shots of finishing sprints!

DT: Yeah, cycling needs more zip line cameras.

I don't even care that much about onboard cameras. I think it's all about like zipline cameras that are going the speed of the rider.

TBD: Another example of that are the CX races in Belgium and the Netherlands. Those seem to be designed almost exclusively for TV. You have an amazing tracking shot across this way and coming back...

DT: And that's what cycling needs. No one cares how many watts those riders are doing. I have to say though, I've been to some of those races, and I was actually pretty underwhelmed by them. The in-person experience to me wasn't very good; they go by and you’re standing around there for a while. By the end of the race, it’s all spread out and there’s not really any pressure building like you get at Red Hook. But it's awesome on TV.

Part II: Sponsorship

We then got into the sponsorship question. This is of particular interest to us as we try to navigate the state of the sport at an amateur, grassroots level: What makes for a good sponsor? What should sponsors expect? David was on a different level in building RHC, but fundamentally, it’s heartening to hear that the best sponsorship relationships are between brands and rights-owners that have shared goals and a shared commitment to growth. Just paying for a deliverable isn’t likely to create a long-term relationship.

TBD: What were sponsors looking for from RHC?

DT: I mean, depends. The sponsors that got a lot out of it were the ones that also activated their sponsorship. As an example: Specialized got a lot out of it because they also put in at least as much effort into their own promotions around the race. Those are the sponsorships that work really well. But for Specialized, it only made sense if it was a championship series of four or more events. Because then they would have this year-long platform to develop products, and build a team, and everything.

Then there's other cycling-industry sponsors that give you, you know… they give you some wheels, and then they don't do anything. And then they're like,”Oh, we're not getting a return out of it!” So that's a major problem in cycling – the way the companies approach events and sponsorships.

I think Specialized did an amazing job with their approach. They were supporting the race. They were helping enable the race to happen. And then they had this, you know, this environment and culture to create a really cool team, and launch creative products around it.

Beyond that, we actually started losing sponsors to teams, because they could sponsor a team at the RHC for much less than they could sponsor the race, which was a challenge.

TBD: What’s it take to make RHC a sustainable brand?

DT: There definitely is a threshold. At some point, sponsors don't care that much about creativity. They just care about people seeing their logo. That's why all the Formula One cars have cool designs, because it's just the corporate branding: “Make it look like the logo.” And that's why Heineken sponsors Formula One: because there's 300 million people seeing their logo.

So if we go in that direction, where those really big sponsors are paying millions of dollars a race, then...yeah, every race has to be televised. There have to be more races, probably 10 races a year, because you have to sustain engagement. So then you're talking about a couple hundred thousand dollars a race, so several million dollars, because if you’re going to be able to raise money, you need at least 10 races a season.

That’s the challenge in making it a serious, world-class sporting championship. Cycling is always struggling. I read your article about funding for Bear Mountain, and it's ridiculously low. That race didn't cost anything to put on.

TBD: And still, folks complain about it!

DT: To me, that doesn't make any sense. You're doing a race in one of the most beautiful places in the world, and you're basically paying nothing for it, and you have all this support…

TBD: So how would you do it differently? Is Neversink the model?

DT: Going back to the sponsorship for Red Hook, if you want to make it this real world-class event, the level of funding is just on another planet.

But then, imagine every race is televised, and we have millions of people watching each one – all of a sudden, the money that's going to come in is going to be huge.

But it takes a huge amount of upfront investment to get to that point. And then keeping it at the same level...it's still a lot of money. When RHC was doing four races, we were probably spending two million a year doing it.

TBD: If someone came to you with a bag of money, and asked you to bring RHC back to life, would you do that?

DT: It would be great to get a bag of money from a sponsor, with no strings attached. But I don’t think that’s how it could work. It would be like an investor, who says, “We want to make this the next X Games.” The potential profitability is going to decide where the sport goes.

TBD: What about a platform sponsor, like Amazon or YouTube?

DT: To the people involved in the Red Hook Crit, it seems like it’s really big. But it's it's actually tiny compared to like something that Amazon would pick up. We talked to Amazon: “I get it, great, but it's too small. You need 10 races and millions of fans already. And then we'll talk about it.”

So you'd have to get investment, either through a big sponsor or through an actual investor, to build it up to the point. The goal for an investor: I'm going to put $20 million into it, and then in 10 years, we're going to sell it, or the media rights are going to be worth $100 million. But it requires a huge amount of like faith. It's a super risky investment.

TBD: Speaking of technology platforms, any thoughts on eSports and cycling?

DT: When it comes to fitness and training, it makes sense to see that side of the sport growth.

But when it comes to racing, I think Zwift is the antichrist.

It’s not really cycling. It’s a good training tool, but it’s not a sporting event to me; it’s not bike racing.

TBD: How do you explain their popularity?

DT: I do think eSports are huge, and there’s a lot of money in it. You have people all over the world racing (and watching) at the same time, paying subscriptions. So from a business standpoint, it makes sense. I just don’t think any of the real culture of bike racing applies.

Our Conclusions

We’re competing for attention

Our interview with David was a powerful reminder that we’re competing in an attention economy – everything we build and market is competing with everything else, for a finite amount of attention. RHC captured attention by bringing together a ton of different people, in no small part because it was a real, world-class sporting event with drama that was immediately understood by even a casual viewer. And as the years went by, it got better and better at building intrigue and pulling people in with media and design that communicated what fans could expect – and with course designs and race production to pay off those expectations.

Video

We’ve got to figure out how to create a coherent video experience for our marquee events. It’s getting cheaper and easier to stream video – note that on a weekend in June, I was able to follow the Harlem Crit through my friends’ instagram feeds. There has to be a way to set up a slightly more professional streaming situation than this without breaking the bank. This shouldn’t be done for sponsors, but instead to rally folks to come experience it live.

Critical mass

Building an event like RHC, or Reading Radsport, or the NECX series – these things take a ton of sustained work over time, and a massive network of partners, sponsors and community allies to support that work. But they’re all businesses too that require a certain amount of funding if they’re to survive. We can’t expect CRCA races to offer the same level of experience, or to attract the same attention, that RHC was able to achieve. But we also need to recognize that our local races are competing with everything, including sitting on the couch, and big transfer rides with buddies. Prioritizing continuous improvement and knowledge-sharing can help each race go a little better than the last, and a strong community can convince people on the fence to jump in.

That’s it for now in our State of Sport series. Thanks for reading, and a huge thank you to David for his time and sharing his views.